Let’s take a look, if you’ll join me, at all of the at-bats that went badly in Kodai Senga’s five-plus-inning, five-run start against the Nationals on Wednesday, a start that turned into a 5-4 loss as Senga, again, failed to record his first win since June.

The first two innings were strong. Then, third inning:

Dylan Crews: Fastball, four consecutive off-speed pitches (three for balls), fastball for ball four (walk)

James Wood: Two off-speed pitches for balls, fastball for strike one, two more off-speed pitches for balls three and four (walk)

CJ Abrams: four consecutive off-speed pitches (RBI single)

Josh Bell: one pitch, an 88.1 mph cutter (sac fly)

On to the fourth inning:

Paul DeJong: cutter for strike one, fastball for strike two, 0-2 sweeper (double)

Crews: fastball for strike one, middle-middle forkball lined to left (RBI double)

Drew Millas: off-speed pitch for strike one, sweeper (RBI triple)

The fifth inning:

Bell: two off-speed pitches to start off the at-bat, fastball for ball two, cutter down the middle (home run)

The sixth inning:

Daylen Lile: Senga runs the count to 2-2 with a mix of fastballs and cutters, then Lile lines a forkball to left (single)

You see the pattern?

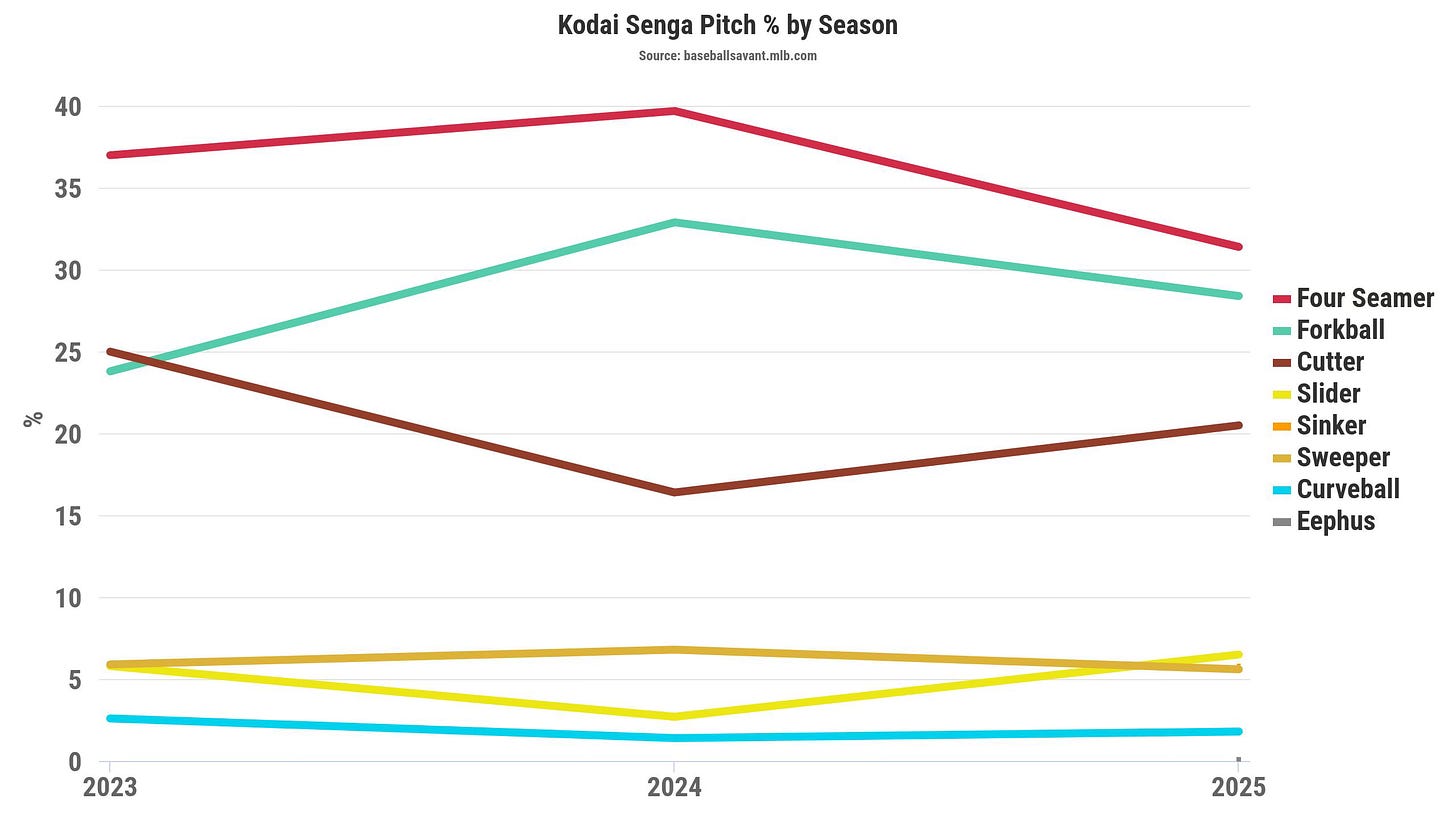

I don’t know whether it’s a new trend emerging or just something that’s always been there slowly creeping into view, but watching the 2025 Mets pitch, I can’t help but notice that fairly often, pitchers seem to temporarily abandon their fastballs and throw one breaking ball after another, and eventually pay for it. It’s evident with Senga, whose four-seam fastball usage is down from 37% in 2023 to 31% this season, and was further down to 26% against Washington. While the season-long numbers don’t jump off the page for most of the staff, the trend has cropped up noticeably throughout the year, and often hasn’t gone well.

Consider last week’s 11-6 loss to the Braves, specifically the nightmarish fourth inning. After David Peterson’s night fell apart, in came Reed Garrett to try to save the day. This season, Garrett is averaging 97.8 mph on his four-seam fastball (which he rarely uses) and 96.9 mph on his sinker (which he uses as his primary fastball).

Garrett entered and faced:

Marcell Ozuna: two sweepers, a sinker, a cutter, and two more sweepers (RBI single)

Ozzie Albies: five consecutive off-speed pitches (strikeout looking)

Sean Murphy: sinker for ball one, sweeper for strike one, sinker for ball two, two cutters for balls three and four (walk)

Michael Harris II: sinker for strike one, splitter in the dirt for ball one, middle-middle cutter (grand slam)

Eli White: sinker, two off-speed pitches, sinker, sweeper (strikeout swinging)

If you’re keeping score at home, that’s six sinkers out of 24 pitches. A 25% fastball rate. For a guy whose sinker is averaging 96.9 mph on the season (and averaged 97.7 mph during that outing).

(Just so we’re clear, I’m not that fastball-favorable; I think Ryne Stanek’s 58.7% four-seamer rate is much too high for a guy whose fastball hasn’t really been getting the job done. He should mix in more breaking balls. But just as with Senga and Garrett, a 25% fastball rate would be too low. There has to be a happy medium. Similarly, pitch selection isn’t the only problem; Senga has also had the traditional issues with velocity and command. But pitch selection matters too. And they’re not unrelated; conventional wisdom and basic intuition say that breaking balls are harder to command than fastballs.)

I won’t get into the analytics, and I’m sure the Mets have convincing reasons for emphasizing off-speed offerings, at least for some pitchers. But at the risk of sounding old-school, I just don’t buy it as a concept. Because if off-speed pitches are the norm, they’re no longer off-speed; they’re the default speed. And once batters are no longer surprised by the sudden decrease in velocity, an off-speed pitch mostly just gives them a bit more time to swing.

Senga’s Ghost Fork might be the most devastating pitch in baseball. But it’s devastating in large part because it’s a surprise. If hitters can easily guess that the forkball is coming, their job isn’t nearly as hard: they either wait for the ball to flutter invitingly down into the zone and take a mighty swing, or they cast a disdainful eye as it lands unbothered in the dirt.

Look, for instance, to Senga’s July 21 start against the Angels, another 25% fastball outing. Senga threw just seven fastballs through the first two innings. So of course Logan O’Hoppe was ready to crush a first-pitch, middle-middle, 90 mph cutter for a home run. In the third, of course Taylor Ward was ready to crush a fourth consecutive off-speed pitch — an 88.5 mph cutter — for a line-drive RBI double. And of course, in the end, Senga went three innings and allowed four runs on four hits and three walks.

Senga isn’t the only culprit — Edwin Díaz, whose fastball can touch triple digits, has put himself in some truly bizarre pitch selection situations, which I’ve occasionally chronicled and for which I’ve invented an innovative PitchCom alternative — but regardless of the perpetrator, the solution is the same. For off-speed pitches to work, they need the threat of a fastball behind them. So mix in the fastball until the batter has to at least be wary of it. Only then should you go back to the slow stuff — and just wait until you see how much better it all works.

Here's why all sends are good.

In the top of the sixth inning against the Nationals, as the Mets trailed 5-4 with the bases loaded and one out, Cedric Mullins hit a shallow fly ball to right field. Dylan Crews caught it; Jeff McNeil stayed put at third; Crews threw the ball in; nothing had changed, except there had been one out, and now there were two. Two pitches later, Luis Torrens grounded out to end the inning.

Consider the probabilities involved.

On the one hand, you have the likelihood of Torrens reaching base (there’s no need to get more complicated than that, since with the bases loaded, a walk, just as much as a hit, brings in a run). On the other, there’s the probability of McNeil tagging at third and beating Crews’ throw home.

(Actually, things could get a tad more complicated if we factor in additional possibilities like extra-base hits and what happens if the inning continues after Torrens, but let’s just focus on the simple version.)

Torrens’ OBP on the season is .275. You can tack on a few points for platoon splits; let’s call the likelihood of his reaching base (and driving in a run) 28%. So if McNeil stays at third, 28% is roughly the likelihood of scoring another run that inning.

What if McNeil tags up and tries to score? It’s a fluid, complicated situation, so I can’t give you any concrete probabilities. But I can give you a few things to keep in mind:

Crews’ throw could come in ten feet off-line either direction, rendering McNeil easily safe; doesn’t that seem to happen about ten times a week, when a runner thinks about tagging but stays put, then the throw turns out to miss the catcher by a mile and it turns out the runner could have waltzed home backwards if he’d only gone for it?

Even if the throw is on-line, it could also go over the catcher’s head;

Even if the throw is pretty good, it could still be far enough off-line that it pulls the catcher away from the plate long enough for McNeil to beat the tag;

Even if the throw isn’t off-line at all, it could come in on a tough bounce and the catcher might not be able to pick the short hop and still get the tag down on time;

Even if the throw is perfect and doesn’t bounce at all and comes in exactly where it should, the catcher, in his haste to put down a quick tag, might not make a clean catch;

Even if the throw is perfect and the catcher catches it perfectly and makes a quick tag, he might illegally block the plate, making McNeil automatically safe; and

Even if none of that happens — Crews’ throw is right on the money, the catcher catches it and puts the tag down, and the entire play is completely legal — McNeil might just beat the throw anyway.

Basically, when a runner tries to tag up and score, he’ll probably be successful unless the throw is almost perfect. If it’s not, even if the ball isn’t hit very far, the throw will probably pull the catcher far enough from the plate that the runner will have time to slide in ahead of the tag. Now, professional outfielders are really good, so the throws usually are almost perfect — but it’s by no means a done deal.

Would McNeil have scored if he’d tried to tag on Mullins’ shallow fly? Probably not! It was, indeed, very shallow, and Crews has a slightly above-average arm. But what’s more likely: that Torrens gets the big hit? Or that — bearing in mind all the potential failure points I’ve outlined — McNeil tags up and scores? Calculate the probabilities on your own and reach a conclusion. I know I lean towards the latter.